Adam, Mirika, Lisa, Gemma and our colleague Simon all got together to think about the top tips we can share with you. Collectively, we are researchers in higher education, within government departments, in schools and in community settings. We have different ethnic heritages and cultural backgrounds. We collectively experience physical, cognitive, and sensory limitations and challenges relating to mental health. Some of us are said to ‘think differently’. Together, we use a wide variety of mobility and communication aids including wheelchairs, walking sticks, captions, screen readers and speech-to-text software.

We talked about the things that collectively help us in our research roles. Simple things. Things that every member of the team can do. We acknowledge that others may have different experiences of disability. Perhaps you may want to use these top tips to start a discussion within your own research team, department, or organisation.

Our top tips are:

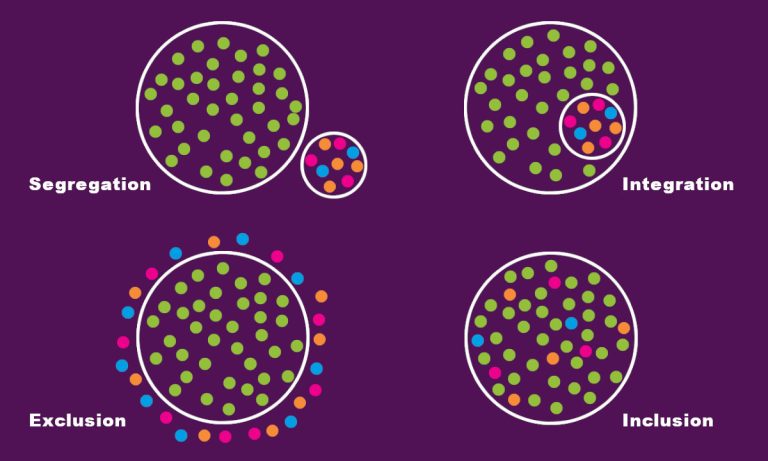

1) Be approachable: Disability is not a personal attribute; it is an experience of being in an inaccessible space or environment (i.e. the social model of disability). As Adam says, “why would you talk about disability with someone who isn’t approachable and understanding”? Be open to recognising that others may have different preferences and/or needs around environments and communication styles. In a research team, it may help to have one person take responsibility around accessibility inclusion, so if anyone has good ideas, they know who to tell. Try not to take things personally or act upset if someone tells you that something could be better or that you’ve made a mistake. It can be really difficult for us to tell someone that there’s an issue with accessing something. It helps to keep an open mind and consider that at times you may need to find ways to address conflicting access needs (for example some people might require a chair without arms but for others chairs with arms are really helpful for getting up and down.) Lisa suggests “having an anonymous way of communicating needs or giving feedback as some people might feel too embarrassed or vulnerable telling people about their needs, especially if they are relating to sensitive or personal issues”.

2) Follow accessibility guidance: This links to being approachable. Firstly, if the environments you are working in (including physical, digital spaces and shared materials) are not accessible, it sends a message that accessibility is not that important. Inversely, by doing what you can to be as inclusive as possible, you send out a message that says you care about accessibility – even if your attempts are not perfect. As Mirika says, “even if I don’t need picture captions, if they are included, I know I can talk to the individual or organisation about accessibility more broadly”. Also, if you find yourself in a position where you feel or have been told that existing accessibility guidance is lacking, don’t hesitate to go beyond the guidance to make resources accessible. Do not be afraid to become a good example of accessibility. As researchers from increasingly diverse backgrounds get involved in research on many topics, your example of making something accessible can act as the beacon which encourages a researcher with experience of disability to engage with a research team.

3) Recognise strengths: Providing opportunities for research teams (and key stakeholders) to get to know each other, is one way to help identify individual and collective strengths. Adam is amazing at innovative ideas, Lisa is extremely creative, most people feel at ease around Simon, and Mirika loves all things methodical. Not saying that we each don’t possess some of these skills (after all, we are researchers). We are saying that, as a team, we know where our strengths are, so we can play to them. For example, with this newsletter Adam led on the idea, Mirika led on the structure and Lisa and Simon considered how the information could be communicated in accessible and meaningful ways. Just one word of caution. When environments are accessible, efficiency improves (of course it does). However, when considering strengths, please consider quality and not just speed.

This leads us to…

4) Be patient and flexible: Some things can take extra time. More time to hunt down material in accessible formats or reformat things into a version that we can access. Even getting around can take longer because not all spaces, travel routes, or modes of transportation are accessible. Even when these things do not take extra time, they often do take more energy and the amount of energy taken to do something can vary from day to day. This means that for some people on some tasks, that means factoring ‘recovery time’ into planning. Planning things in advance is helpful to reduce last-minute deadlines. It’s also incredibly important to be flexible. For example, if you’ve agreed to meet in-person to discuss some research, but then are told by the researcher that they are unable to meet because they’ve run out of energy for the day, be open to meeting on Zoom/Teams instead. We also know structures of funding do not always allow for extra time to accommodate researchers with experience of disability. The CRSJ, the Resilience Revolution and Boingboing have collectively campaigned for additional time to enable those often excluded, to be included in research.

5) Speak up: If you spot something could be more accessible, say so. Don’t wait for someone that needs something changed to have to ask for it. Remember, that it is highly likely that that ‘reasonable adjustment’ has been seen as ‘unreasonable’ in the past. For example, have you ever asked yourself why music festivals (as standard) are more accessible than academic conferences? It is certainly not because researchers with experiences of disability have not raised it as an issue, we can assure you! If you feel uncomfortable raising an issue because you fear it may get shouted down by those in power, use your community e.g. disability or mental health and wellbeing organisations/forums. They can provide a source of support and actively work to amplify the voices of those that are disempowered. If there is no active community available, don’t hesitate to build your own. Through this process you may discover that many people are experiencing similar problems as a result of inaccessibility, which can provide a sense of motivation to keep going if things get difficult. We have put a lot of focus on designing our International Resilience Revolution Conference to be more accessible.

An icon of a magnifying glass looking at data graphs to represent research

6) Adopt Inclusive Data Collection Tools & Approaches: We are all researchers and we want to conduct research that is accessible as possible. Almost all of us, however, have not contributed to research as participants because the study was not designed with accessibility in mind. Adam says, “I am less likely to complete something if I don’t think accessibility is important”. Some of us specifically want to know experience of disability will be considered in the analysis. This is because some feel our responses more may be different to those that do not experience disability. Including statements around accessibility in participant information sheets may help. Including a question around experiences of disability as one of the first research questions may also be helpful. Collectively, we found surveys hardest to complete. Using software that enables questions to be read aloud, working with gatekeepers to provide extra support, providing questions in alternative format (i.e. paper, telephone) may also help. However, it may still take more time and more energy for people with experiences of disability to take part in research.

7) Value meaningful collaboration with people experiencing disability: Often those experiencing disability are invited to comment on research that relates to them in some way, but their involvement can sometimes be tokenistic: a box-ticking exercise. We are strong advocates for meaningful co-production. Researchers and members of the public that share experiences of disability must be included at all stages of the research, in accessible ways. We feel it’s important to make sure members of the public are paid for their time and expertise and accredited for their work. This is especially true when research relates to communities experiencing disability, but we argue that research on any topic benefits from being more inclusive.

8) Protect your own health and wellbeing – Challenging inequality can be very tiring mentally, physically and emotionally. Through the process of working to make things more accessible, no one expects you to be a one-person army for accessibility 24/7. Be sure to take time away from challenging inaccessibility to engage in hobbies, relax and rejuvenate yourself. As Simon says, “Remember that you cannot drink from an empty glass, be sure to recharge your own mental, physical and emotional energies on a regular basis. This will ensure that we can all continue working towards a more accessible future.”